The compromise immigration bill, including the AgJOBS element, is getting another chance in the Senate. Even if it passes the Senate, it has an uncertain future in the House of Representatives, with House republicans warning the President not to push too hard. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi has notably not committed to the bill and says she won’t even bring it for a vote if it doesn’t have 50 to 70 House Republicans signed on.

Although AgJOBS itself is a big plus for the produce industry, one wonders if in the end the bill will actually help the trade’s labor situation. After all, the profile of the typical legal immigrant will change with the shift to an education and achievement point system counting for more than family unification, and immigrants that fit the new criteria may have less interest in produce jobs than current legal immigrants.

The bill’s border security efforts to reduce illegal immigration may work and thus reduce the supply of illegal immigrants.

Plus the legalization of the estimated 12 million illegals will allow many illegals presently employed in the industry to shift to other, more stable, more lucrative or less physically taxing professions. AgJOBS will offset some of this but one wonders if net-net-net the bill will actually produce more or less labor for the produce industry?

We really need more emphasis on how the industry can survive and thrive if labor becomes scarce and more expensive. The logical approach is to use our facility with technology to develop mechanical harvesting techniques.

We’ve run pieces such as Reducing Labor With Technology, before and received a letter from an industry leader which we published here that included this point:

I’ve long contended that the agricultural community is hooked on the drug of cheap labor. In the 60’s, people were mechanically harvesting certain vegetables for Campbell’s Soup. They had to quit doing it because labor was so cheap — they couldn’t beat the cheap labor rates — and the machine wasn’t efficient enough to overcome it. The point is, it was being contemplated 40 years ago, and it should have been an industry-wide effort ever since.

We haven’t worked on mechanization and automation in this industry because we have had no motivation to do so. Now, with fear of labor shortages, we see a frenetic pace of R&D on mechanical harvesters. I’m already hearing tales of at least four companies that will be mechanically harvesting lettuce in Yuma with less than 50% of the labor previously needed, and they also claim better quality! And this is only the start of an industry revolution.

Now Vision Robotics Corporation has been hard at work developing tools for mechanical harvesting. The idea is to use a kind of “scouting robot” that will go out into a field and draw a digital map of what needs to be done. This could include weeding, trimming, etc. It also would map out the ripe fruit for harvesting. Then mechanical harvesting equipment would be brought in.

This is crucial because previous mechanical harvesting machines were too slow. This is because, as Vision Robotics explains it, the harvesters approached a tree as a human being would. The machine would find one piece of ripe fruit, harvest it, then look for another, then harvest it, etc. The scouting robot would allow a multi-armed harvester to simultaneously harvest many pieces of fruit.

This is a sketch from the patent application of the scouting robot:

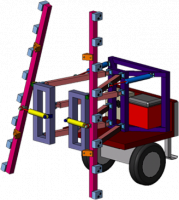

These are 3-D models of mechanical equipment proposed for the apple and orange harvesting and for grape pruning. Click on each photo and you can see additional photos:

Our vision systems are first used to scan and identify apples within an orchard. Cameras placed at the end of long scanning booms use arrays of stereoscopic cameras to create a virtual 3D image of the entire apple tree. The positions and sizes of the apples are stored and passed onto the harvesting arms. Immediately following the scanning process, a series of long reticulating arms are maneuvered to gracefully pick each apple quickly, efficiently, and economically.

Our vision systems are first used to scan and identify oranges within a grove. Scanning heads placed at the end of multi-axis arms use arrays of stereoscopic cameras to create a virtual 3D image of the entire orange tree. The positions and sizes of the oranges are stored and passed onto the harvesting arms. Immediately following the scanning process, eight long reticulating arms are maneuvered to gracefully pick each orange quickly, efficiently, and economically.

At the end of each season, workers must go out into a vineyard and meticulously trim every single vine at a precise angle and location in order for the following year.

The question is: is this science or science fiction?

Well important industry institutions are backing Vision Robotics Corporation. Wired magazine reports that the California Citrus Research Board has anted up almost $1 million and Ted Baskin, president of the board, has estimated that it will take $5 million more to finish the job. The Washington Tree Fruit Commission also is investing in the project. Other ag groups are in discussions.

In the past there have been many obstacles. Wired reports that Cesar Chavez fought against Federal funding:

…it wasn’t just technological challenges that held back previous attempts at building a mechanical harvester –- politics got involved, too. Cesar Chavez, the legendary leader of the United Farm Workers, began a campaign against mechanization back in 1978.

Chavez was outraged that the federal government was funding research and development on agricultural machines, but not spending any money to aid the farm workers who would be displaced. In the ’80s, that simmering anger merged with a growing realization that the technology was nowhere near ready, and government funding dried up.

Vision Robotics says it still doesn’t pay:

Despite the fact that an assortment of researchers have been working on both robotic automation of fresh fruit care and harvesting for decades, there remains no viable, cost-effective approach towards robotic mechanization. The cost of automated harvesting is based on picking speed; the faster the better. Any robot operating in an orchard will have multiple arms to operate efficiently, yet coordinating a multi-arm picker is difficult

Yet whether it “pays” or not depends on how we figure the cost. Obviously, if the labor situation gets tighter, wages will go up and the machines become more feasible.

Yet as a society, we may not be calculating the true cost of the migrant labor. That same letter that included the quote we excerpted above about mechanical harvesting also contained this analysis:

…we haven’t attributed the correct cost to our cheap labor. Thirty percent of California prison inmates are in the country illegally. There are 20 murders per year in Salinas, a city of 150,000 people. The city spends almost $1 million on a gang task force every year. These are social costs that are borne by all the citizens of the city and state, and aren’t accounted for in the cost of the produce.

Our letter writer also said this:

Where there’s a will, there is a way. We haven’t had the will because there was no need to abandon our reliance on cheap labor and find a better way of doing things.

Perhaps the debate over immigration will be the catalyst we have needed to change. The industry owes some thanks to California Citrus Research Board and Washington Tree Fruit Commission for investing in this very likely future.